Future Face ID could map a user’s veins to foil ‘evil twin’ attack

Apple wants to improve the security of Face ID and other visual-based biometric systems to eliminate the so-called “twin problem,” by taking advantage of the unique and hard to copy patterns of veins that reside under the skin.

Biometric security systems like Face ID and Touch ID offer protection for user data in a relatively easy to understand package. It is also one that is also simple to use, as the user doesn’t need to remember passwords or codes since their face or fingerprint effectively are their account credentials.

While security is good, they are still fallible by a number of areas, such as having a very small false-positive rate, which in the case of Face ID is in the realm of one in a million.

There are also issues with people being able to create highly complex masks to fool Face ID, typically in a fashion far beyond the capabilities of a normal person. Lastly, there’s the “twin problem,” where facial recognition systems like Face ID could grant access for people who look extremely alike, such as twins or family members.

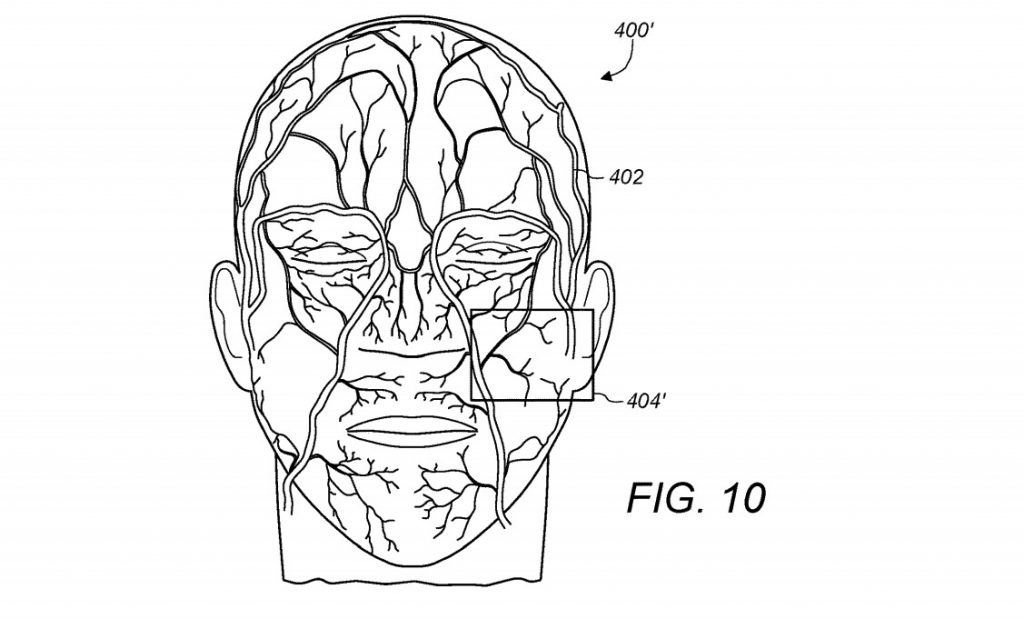

In a patent granted by the US Patent and Trademark Office on Tuesday titled “Vein matching for difficult biometric authentication cases,” Apple proposes that the answer is more than skin deep. Specifically, a few millimeters below the skin, as it suggests that veins could be used as an identifier.

While facial features can be easily copied, vein patterns differ wildly between individuals, even twins. As they are also below the skin and occupy 3D space, it is also extremely difficult to create a counterfeit face that takes into account the vein structure without either the extreme cooperation of the subject, or medically invasive maneuvers.

The system consists of creating a 3D map of a user’s veins using sub-epidermal imagery techniques, such as an infrared sensor in a camera capturing flood and speckle patterns from infrared illuminators lighting up the user’s face. This is somewhat similar to how Face ID currently works, in that infrared light is emitted in patterns on a user’s face and read by an imaging device, but Apple’s patent is specific about detecting the veins instead of the exterior.

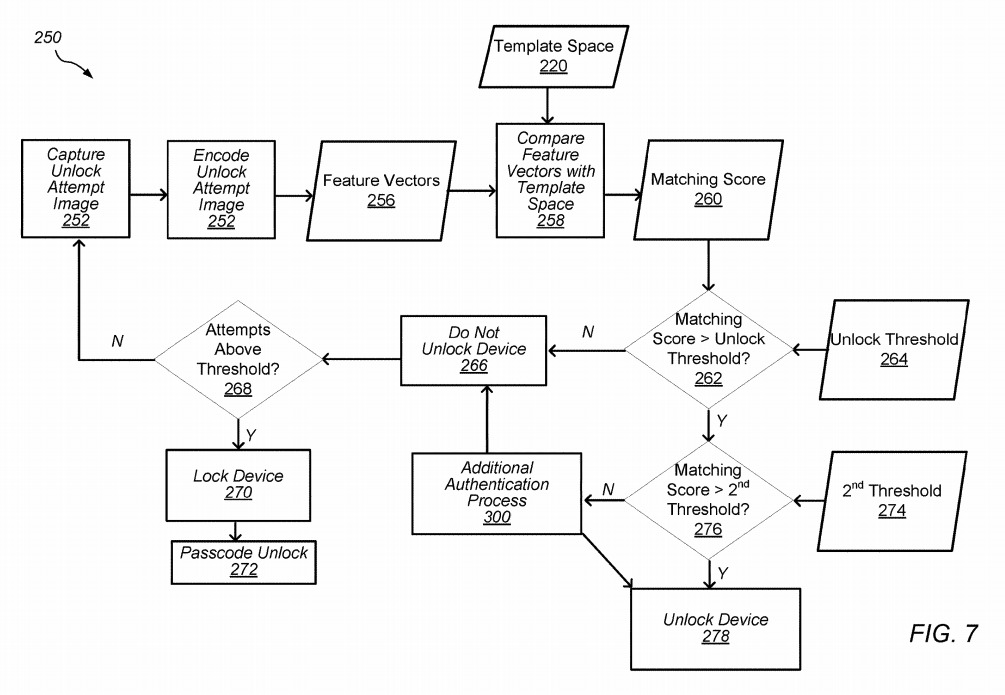

Like other biometric methods, the system has to determine if there is a close-enough match between the scanned data and previously-taken version used to register the user. If the match is close enough, the system effectively confirms the user is authorized, and access is granted.

Apple files numerous patent applications on a weekly basis, but while the ideas offer areas of interest for Apple’s research and development efforts, it does not guarantee that the idea will appear in a future product or service.

The patent lists its inventors as Micah P. Kalscheur and Feng Tang, and was filed in February 2018. The patent application first surfaced in searches in March 2019.

Earlier Work

Apple has looked into many different ways it can take advantage of a person’s veins for a variety of purposes. A related patent granted on May 2018 for “Vein imaging using detection of pulsed radiation” reuses the concept of infrared emission and reception to monitor for blood vessel patterns, but adds time-of-flight calculations of pulses to produce a three-dimensional map.

A similar concept has also been mused for the Apple Watch, using a light field camera to detect patterns of veins, arteries, blood perfusion in the skin and tendons, and hair follicle patterns, among other elements, that could uniquely identify a user. Vein scanning in an Apple Watch may also be used to detect no-touch gestures, such as hand or finger movements, that could trigger actions on the wearable device.

Apple is also looking into how a user’s palm veins could be analyzed as part of Touch ID-style recognition, except the user presses the entire screen of the device with their hand.